The Warmley Works of William Champion

by Reg HarrisAfter Abraham DARBY left the brass mills at Baptist Mills, Nehemiah CHAMPION, a Bristol Quaker, assumed leadership. He was son of Nehemiah, a Bristol merchant who lived at 68 Old Market, who traded, with his son Richard, with Abraham Darby of Coalbrookdale, buying and re-selling his hollow-ware pots and pig iron. In 1723 Nehemiah held a patent for a new method of preparing copper for use in brass making which was used at Baptist Mills.

Nehemiah had three sons, the eldest being John (1705-1794), Nehemiah (1709-1782) and the youngest William (1710-1789). William travelled extensively to the continent to learn the art of brass making, returning to Bristol in 1730. He then experimented at Baptist Mills with producing metalic zinc sulphide (which at that time was imported from India and Asia at a high price) from English calamine. He was the first man, in this country, to produce zinc on a commercial scale and it took him about six years to achieve success. He obtained a patent for his method in July 1738 and his system remained in production for over 100 years.

William established a factory after 1738 with the assistance of capital from his father. William's factory was at Babers Tower in Back Lane just off Old Market in Bristol. He produced about 200 tons of zinc at a cost of £7000 but, unfortunately for him, his factory was causing a nuisance in this built up area, which was reported to the Council in September 1742. He later told the Council the premises had been pulled down and the site was to be redeveloped. At the same time he was making plans to build a new works at Warmley whilst still a member of the Bristol Brass Company.

In 1742 father Nehemiah married a widow, Martha VANDEWALL (a sister of Thomas GOLDNEY), and moved to a new home in Clifton opposite the family home of the Goldneys. This cemented a relationship with the Goldney family, which was to last for many years.

In 1746 Champion broke away from the Bristol Brass & Copper Co. and formed the partnership called the Warmley Company for "the making of copper and brass, spelter and various utensils in copper and brass". His chief objective in founding the new company was to exploit his patent for making spelter or zinc from calamine. William recruited workmen from the continent who agreed to come if they could have free exercise of their religion for which permission was obtained.

At this time large quantities of spelter were being imported from the East Indies, and desperate efforts were made by the merchants to crush him. Before his invention spelter had been selling at £260 per ton, but the Bristol importers undercut him until in 1750 they were selling it at £48 to discourage him from continuing to smelt zinc. Although they were losing money at this price they made it impossible for William to sell his stock at a profit - he lost about £4000 on the cost of his stock.

The early partners in this venture were Sampson LLOYD, a Quaker ironfounder of Birmingham who had married William's sister Rachel, Thomas GOLDNEY, a Bristol Quaker, and Thomas CROSBY a Quaker (married to Charles HARTFORD's widow, Rachel nee REEVE), and others. These Quakers were all related to the Champion family. The shares in the new Company were divided eight ways and the partners contributed over £1000 each. Because some of the partners were members of The Bristol Brass Co. it was the cause of ill feeling, which later developed into acrimony.

Champion, who had now erected large works for the manufacture of Spelter, petitioned for an extension of his patent for smelting zinc for another fourteen years; and he was supported in his petition by certain people in Birmingham and Wolverhampton, who used great quantities of spelter and affirmed that his was as good as any brought from the East Indies. It was accordingly suggested that a Bill be brought in, but it was not proceeded with on account of the opposition it created.

During 1747 the cast iron equipment needed for the new works was being bought from the Darby Ironworks at Coalbrookdale. As the work progressed the partners were called on to invest more capital, which they did by making loans at interest.

Father Nehemiah died in August 1747 before the new works commenced production. In his will he left legacies to all his partners and workers at Warmley. William's brother John inherited his father's shares in Baptist Mills but had his own works at Holywell in Wales and was involved in several copper mines there so was not involved in the Warmley venture.

However, William intended to make everything from smelting the metal to the finished products of copper and brass and, by 1748, the new Company was buying Cornish copper ore for the new works which was now ready for production. William used the process developed by his father to prepare the copper to be converted to brass.

In February 1750 William applied to the Commons for some form of recompense for the losses he had suffered in making the first home produced zinc. He was concerned to get an extension of his patent rights for the process. A Commons committee reported that this should be granted but the Bristol merchants brought a counter petition and the patent extension was later abandoned.

Meanwhile the Warmley works were being expanded - a new steam engine was installed to return water, used by the waterwheels, to the mill pond, and a bigger dam was constructed to hold more water. The Bristol Journal reported on the steam engine on 13.9.1749. The new engine cost £2000 and used £300 worth of coal a year. William by now had the most complete works in the kingdom. Profits were increasing and in 1757 the dividends paid to the partners were increased.

In 1761 ELLACOMBE states that there was a windmill for crushing ore and two horse mills in addition to the waterwheels and steam engine. There were 40 furnaces erected and also 25 houses, for the imported workers, and shops on the premises. In this year another steam engine was installed, the parts being bought from Coalbrookdale for £600.

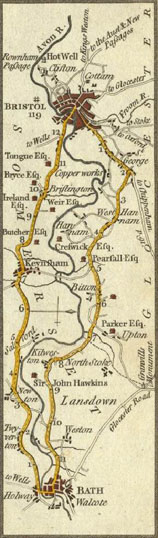

William was planning to build new smelting furnaces in Kingswood but the cost was beyond the resources of the existing partners and he was trying to find new partners to inject capital. He approached local coal owners - Charles BRAGGE of Cleeve Hill, Norbonne BERKELEY and Charles WHITTUCK of Hanham Hall. They did not like The Bristol Brass Co. and William hoped to get coal from them at a discount. He got the co-operation of the coal owners and they helped him find a site and to build the new works "near the sign of the Horseshoe". There was to be £100,000 capital in 800 shares at £125 each. The new furnaces were built in 1761. By 1765 the Kingswood works were running into financial difficulties as only £29000 had been subscribed and money had been borrowed at high interest. They also had a forge at Kelston near the River Avon and a battery mill at Bitton on the River Boyd.

In 1763 William was again short of capital and Thomas Goldney transfered a loan of £1200 from another of his works, The Bristol Lead Co., at interest. He then loaned a further £1500 from his own capital. In 1765 the dividend paid was doubled from that paid in 1763. The money borrowed from The Bristol Lead Co. was paid back.

By 1765 William must have had some spare capital to invest because he built a wet dock on the eastern bank of the Avon near Rownham able to hold 36 of the largest ships which frequented the port of Bristol. This became known as The Great Dock but was not a success as the ship owners did not use it. The cost of the construction depleted his resources and as there was no income from it he had to offer the docks for sale in 1770. It was bought by The Merchant Venturers for £1770 and became known as The Merchants Dock.

From time to time the Bristol council looked at ways to make the Bristol docks a floating harbour to prevent ships being stranded on the mud of the river banks when the tide went out. In 1767 William Champion put forward a proposal to build lock gates across the Avon below the point where the Frome joined it to make the whole Bristol port a floating harbour. Unfortunately, the cost at £30-37,000 was too great and the plan was dropped.

Nevertheless, the Warmley Company carried on operations with great vigour, and in 1767 the partners claimed to have a capital of £200,000 and to give employment to about 2,000 people. In the previous year Champion had successfully petitioned for the sole use for fourteen years of his invention "of refining copper for making brass by wrought iron, and of making zinc from a mineral called Black Jack or Brazil, instead of calamy or lapis calaminaris; and for manufacturing brass into wire by stone or Pit Coal instead of wood now used".

This growing prosperity led the Company to seek a charter of incorporation in 1767. The members were have "perpetual succession", and to be able to increase their capital to £400,000, consisting of transferable devisible shares. It was also desired that the shares of each person in the Company should be deemed a personal not a real estate. The trouble they alleged was that, under the "Bubble Act" of 1719, voluntary companies were not permitted to have transferable stock. All the other brass and copper companies petitioned vehemently against the proposal: They complained that the Warmley Company was not worthy of special treatment since it had not ventured any new or hazardous branches of commerce, but had built upon foundations already made good at the expense of others; that the trade had reached its full growth, that no further extension could be expected. If the shareholders concerned were incorporated, they argued, they would be in a position to command the market for raw material and so would make themselves masters of the trade while, "at the same time, they might be tempted to apply themselves more to the means of raising the nominal value of their stock and make large dividends, than to that industry which is so necessary to commerce".

The pin-makers of Gloucester were convinced that the grant of a charter would be detrimental to their trade, and that so large a capital as £30,000, which the Warmley Company proposed to employ in the pin-making branch of their business, would draw off the trade from their town, and so deprive about 1,200 men of a livelihood. They would be subjected, they maintained, to oppression and monopoly. The allegations contained in the various protests, made against the grant of a charter, were, for the most part, unfounded.

The Warmley Works, where "the whole process of the copper and brass manufacture was exhibited from the smelting of the ore to the forming it into plates, wire, pans, vessels, pins, etc." was probably the most up-to-date and most efficient works in the country. In addition, there was a considerable pin manufactory, where the latest machines and methods were employed. It is very probable, however, that the rapid extension of these works involved the undertakers in acute financial perplexities; and there seem to have been many debts outstanding.

It is abundantly clear that the works owned by the various brass and copper companies were "factories" and that large numbers of wage earners were employed. It would be useful to try to obtain some clear conception of the actual size of the industrial works. In 1767 the Warmley Company, which had a much larger capital than any of the other undertakings of the same time, claimed to give employment about 2,000 persons in the making of copper, brass, spelter, and various utensils in copper and brass. It is just possible that this figure may include the pin-makers in Gloucester, who obtained their brass wire from the Company, (and it was said that there were 1,200 of them), and the miners employed in the local pits.

There is no doubt, however, that the works was the most extensive of its kind in England. The capital of the concern was £200,000, and, when, in 1767 it was proposed to employ £30,000 in the pin-making branch of the business, the pin-makers of Gloucester petitioned against this extension, declaring that the investment of so large a capital would draw off the trade from their town. Taking these considerations into account, therefore, it would seem that large numbers of wage earners were employed at Warmley, and, judging from the great amount of specialisation that existed, it is perhaps not far short of the truth to say that in the different branches of the undertaking, all of them situated at the same place, at least 600 people were employed (many of the women and girls in their own homes).

In 1766 more capital was called for from the partners and again in 1767. William's interest was in the technical side of the business and he was not a good manager of the finances. He was described by contemporaries as of short temper and rude manners.

During 1767 William took out a further patent for the brass works, which covered the refining of copper by using wrought iron pipes in order to remove arsenic from the smelt; using pit coal instead of charcoal to make brass wire and using zinc sulphide instead of calamine to make his brass.

Purchases of Cornish copper ore were greatly increased and he started the manufacture of pins. These were made in the building with the clock tower, which still stands, and by outworkers, employing several hundred women and girls. With the increase in production William had installed an extra steam engine.

In order to further his application for incorporation he did a complete inventory of the Companies' worth which showed that the total capital employed in the works was about £300,000 of which the members of the Company had advanced £100,000 and £200,000 had been borrowed.

In April 1767 the Commons issued a warrant that gave authority for the preparation of Charter of Incorporation. His competitors petitioned that this should not go ahead as this would damage their interests. They also claimed that they had made a similar application four years before which had not met with success. This led to lengthy legal proceedings and the Attorney General concluded there was no objection in law and a further warrant was issued in October 1767. This led to increased opposition by the competitors who claimed that the Warmley Company would become a monopoly and their heavy debts might cause the Company to disintegrate. By March 1768 the opposition had won and no further steps were taken to obtain a Charter.

In April 1768 William's partners discovered that, knowing that collapse was inevitable, he had tried to withdraw part of his capital without permission and he was dismissed from the Company. Charles BRAGGE wanted to keep the works running on a more moderate scale to regain at least part of their losses but none of the partners were in a position to put new capital in. The partners tried to carry on the Works without success. Because he could not pay his debts William Champion was declared bankrupt and, on 11th March 1769 the Warmley works were offered for sale in Felix Farley's Bristol Journal.

Due to the American War the price of tar greatly increased. This was used extensively on ships and great efforts were made to discover a substitute. In Sarah Farley's Journal on 29th April 1780 an advertisement appeared saying that the family of a person deceased offered for sale his invention of a method of making English tar. Information respecting this was to obtained from Mr. William Champion. Shortly afterwards works were established in the city for extracting tar from coal.

In 1789 the Warmley Works were sold, and soon passed into the hands of the Harford & Bristol Copper Company who were happy to obtain Champion's patents. They continued to be used for the manufacture of copper and brass till 1809, but the works were never used as extensively as before and a few years later they were discontinued. The Bitton Battery Mill was sold off in 1825 and became a paper mill. Unemployment varied between 10-20% of the work force.

Back to top of page